Overview

This lesson introduces you to the basics of Docker.

Outcomes

After reading this lesson, you should be comfortable...

- pulling images

- launching containers

- using bind mounts to share and persist data

- forwarding ports

Prerequisites

This tutorial assumes that ...

- You have a working Ubuntu LTS installation

- You are comfortable with the basics of the Linux command line

- You are familiar with the concept of containerization

- You have a working docker installation

Background

What is Docker?

Docker is both a software company and a software implementation of containerization. The company helped establish the Open Container Initiative (OCI), A Linux Foundation project which defines industry standards for container technlogy.

While docker software isn't the only implementation of containerization used today, at the time of this writing, it is the most ubiquitous container technology.

Images vs containers

At a conceptual level, there are two important concepts that we'll cover: images and containers.

Images

An image can be thought of as a snapshot of a particular configuration which defines and bundles all a) dependencies, b) required data, and c) any default launch behaviors.

- Images are immutable (i.e., they do not change). The only way to alter an image is to create a new image by extending the old one.

- Docker image definitions are specified in a special file called a Dockerfile.

- Images can be shared. Most commonly, images are exchanged by pushing (publishing) and pulling to and from registries such as DockerHub.

Containers

A container is an instance1 of an image.

- Containers are mutable. They can be altered while running, but these changes don't persist when the container is stopped.

Mounted volumes are used to save the output of a container's process or provide the container with data not included in its parent image (ex. database files)

Docker hands-on

Pulling an image from DockerHub

To pull an image from the DockerHub registry, you need to specify the owner of the image, the name of the repository, and a tag (version).

<owner>/<repo>:<tag>

latest will be used. latest is the tag associated with the most recent build published. While always attempting to use the latest version may sound appealing, not denoting a specific version can lead to problems. For example, often major version releases involves breaking changes breaking changes. Using latest may make it harder to notice such releases.

If you want to avoid nasty surprises and emphasize replicability, it's better to use an explicit version.

Let's download the following image which defines a development environment for Python 3.7:

docker pull uazhlt/python-playground:latestNote that docker retrieves the image in layers. Each layer is sort of a miniature snapshot of the changes run up until some point in the image definition. Future changes to an image (or a related image) may share layers. In such cases, docker will avoid unecessarily downloading those layers if they're already present locally.

Running a container

By default, containers launched using this image start up a jupyter notebook server.

docker run -it uazhlt/python-playground:latest

[I 09:52:02.260 NotebookApp] Writing notebook server cookie secret to /root/.local/share/jupyter/runtime/notebook_cookie_secret

[W 09:52:02.564 NotebookApp] All authentication is disabled. Anyone who can connect to this server will be able to run code.

[I 09:52:02.596 NotebookApp] [jupyter_nbextensions_configurator] enabled 0.4.1

[I 09:52:02.596 NotebookApp] Serving notebooks from local directory: /app

[I 09:52:02.596 NotebookApp] Jupyter Notebook 6.1.0 is running at:

[I 09:52:02.597 NotebookApp] http://2e7741de1b55:9999/

[I 09:52:02.598 NotebookApp] Use Control-C to stop this server and shut down all kernels (twice to skip confirmation).The -it option used in the command above allows us to easily interact (ex. kill via ctrl+c) with the container.

The container will launch and claim its service is available on port2 9999; however, navigating to localhost:9999 in your web browser will not work. What's wrong?

Let's kill this container using ctrl-c and make some adjustments...

Port forwarding

The container in our example runs in an isolated network. In order to access the service described, we need to expose its 9999 port and map it to a local port:

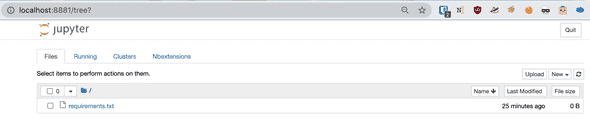

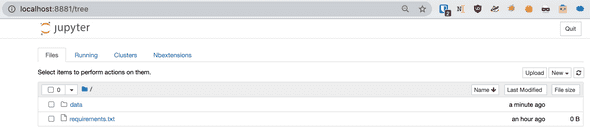

docker run -it -p 8881:9999 uazhlt/python-playground:latest-p 8881:9999 defines a port mapping. localhost:8881 will point to localhost:9999 in the container. With this change, we're able to access the jupyter notebook server!

It looks like there aren't very many files in the container. What if we wanted to a directory called dataset?

Let's kill this container using ctrl-c and make some adjustments...

Volumes

There are several ways to persist data when using containers, but we'll focus on bind mounts.

Bind mounts are a way of persisting and sharing data between host and container by mapping a location on the host file system to a location inside a container.

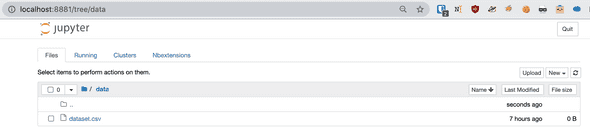

Imagine we have a directory called ~/my-data containing a file called dataset.csv and we want to make the entire directory available inside of the container for reading and writing. That way we have the output (ex. trained model, normalized data, etc.) locally once the container has finished processing it. We can use the -v or volume option to achieve this:

docker run -it -p 8881:9999 -v "$HOME/my-data:/app/data" uazhlt/python-playground:latest/app/data in the command above indicates that inside the container, mounted my-data will be called data and be found under /app.

There's our data directory in the running container. If we look inside that directory, we can see dataset.csv is present:

docker run -it -p 8881:9999 -v "$HOME/my-data:/app/data" -v "$HOME/another/directory:/app/data-2" uazhlt/python-playground:latestViewing a list of running containers

To view a list of running containers, try docker ps:

docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

2e7741de1b55 uazhlt/python-playground:latest "/bin/bash /usr/loca…" 8 minutes ago Up 8 minutes 0.0.0.0:8881->9999/tcp crazy_fermiThe output shows us that we have one running container launched using the uazhlt/python-playground:latest image. We can also see a summary of port mappings and the command the container executed when it was run. The ID field is helpful if we need to interact with a running container (ex. killing (destroying) a container, connecting to the container, etc.).

Kill a running container

If a container becomes unresponsive, you may need to kill it. To do so, we'll need the ID of the container. Open a tab in your terminal and run the following command:

docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

2e7741de1b55 uazhlt/python-playground:latest "/bin/bash /usr/loca…" 8 minutes ago Up 8 minutes 0.0.0.0:8881->9999/tcp crazy_fermiIn this example, we have only one running container. Its ID is 2e7741de1b55. To kill this container, you would run the following command:

docker kill 2e7741de1b55Running containers with non-default commands

Images define default commands to be executed when a container is launched, but you can override these commands. For example, let's launch a container running an iPython interpreter using the same docker image as before:

docker run -it uazhlt/python-playground:latest ipythonThe command that follows the image name denotes what we want to run when launching.

To exit, type exit.

Removing old images and containers

Periodically, you may wish to remove old docker images to save space on your hard drive. To do so, run the following command:

docker system prune --allNext steps

If you've folllowed along, hopefully it's become clear how a container can serve as a portable development environment.

Practice

- Practice what you've learned by launching an instance of

uazhlt/python-playground:latest- map your local port 7878 to 9999 in the container.

- bind mount a directory of your choice under

/app(ex./app/docker-data-practice) and confirm that you can access it from the container.

- The image vs container distinction is closely related to that of classes vs instances in Object Oriented Programming.↩